Gormenghast

One – Eighteen (p373 – p467)

.

.

This week’s Gormenghast discussion is written by Birdie, a blogger who reviews literary fiction with emphasis on British writers.

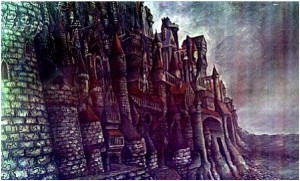

The beginning of Gormenghast, while retaining the absurdity of Titus Groan, has a slightly different feel to it. I ascribe this difference to the fact that we get to see inside the characters’ heads a bit more often and in more detail. In Titus Groan, we never really got the opportunity to understand Lord Sepulchrave’s motives, or the Countess’s, or even Prunesquallor’s, and it was the very last section of the book before we got to see into Flay’s personality (with the consequence that I sorely miss him in this text). We did see into Steerpike and Fuchsia a bit more, but in this second book of the series we are meant to move into the world a little more.

Titus Groan was largely about viewing the world of Gormenghast from the outside: the first viewpoint we could really be said to follow was Steerpike’s and he was still an outsider to the culture of Gormenghast at the time. We are presented with the characters almost as Steerpike sees them. In other words, we see them from a more distant and sociological perspective. This perspective accounts for the difficulty many of us had in forming sympathetic relationships to the characters. In this second novel, Steerpike has established himself as an inevitability, training under Barquentine, spying on many of the castle inmates, engineering the disappearance of the twins and controlling them through terror. While he becomes a constant force in the castle, we as readers need his viewpoint less, and we gravitate toward the interiority of other characters just when Steerpike’s shallowness and sadism toward the aunts is demonstrated.

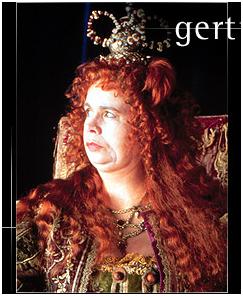

I find the sections of Gertrude’s thoughts particularly interesting, since she seems to have been cast as singularly thought-less in the first novel. But in Gormenghast, we see her struggling to turn on her brain after years of neglect and we get an idea of what her internal character is like. I have several questions that revolve around the Countess: What is it that has awoken the mistrust in her mind/heart? Does she sense Steerpike’s perfidy or is she simply reacting to the change necessitated by the loss of Lord Sepulchrave, Sourdust, Flay, Swelter, and the Twins? We know that her animal/base instincts are incredibly strong since she has a greater affinity for animals and nature than for humans. What instinct, then, leads her to trust Prunesquallor?

Gertrude does not like change, which is unsurprising since the entire absurdist edifice of Gormenghast is built on the unchanging nature of out-dated ritual. What is interesting is the way that other characters who might not have such a strong personal interest in this ritual are blindly loyal and extremely dedicated to the status quo. In particular I’m thinking of the Professors of Gormenghast here, whose days are dictated as much by ritual as those of the seventy-sixth Earl had been, and who are also every bit as averse to change:

There had once been talk of progress by a young member of a bygone staff, but he had been instantly banished. (page 490)

What do you think Peake is doing with these characters? Is this simply more demonstration of the dangers of inertia or is Peake making a larger point about the educational system, not only of Gormenghast, but of the public schools that breed a sort of traditional mentality? Also, the narrator mentions several times that Titus is to be treated the same as the other castle whelps , presumably in order for him to understand multiple types of relationships and to humble him a bit. But we have not seen Titus interact with any of his school fellows. And though he is supposed to be treated the same, would there have been a school-wide search for any boy other than the young Earl?

Finally, we get to see inside Titus’s mind quite explicitly. The boy seems to think primarily in colours and images rather than in logical thoughts. His reflections on the marble on his desk seem related in this way to his discovery of the brightly coloured room in the castle and to his view of the separate copses as distinct from his vantage point on Gormenghast mountain. What does this visual sense of apprehending the world tell us about Titus?

Other opinions on this section: